I am on a mission to end Bible Translation Tribalism. If you don’t know what I mean by “Translation Tribalism,” see if any of these tribal stereotypes (some borrowed from another blogger) ring true for you:

I am on a mission to end Bible Translation Tribalism. If you don’t know what I mean by “Translation Tribalism,” see if any of these tribal stereotypes (some borrowed from another blogger) ring true for you:

- The NIV 2011 is the Bible of the broad swath of centrist evangelicals.

- The TNIV is the Bible of egalitarian leftist evangelicals.

- The ESV is the Bible of complementarian, conservative, neo-Reformed evangelicals.

- The NASB is the Bible of conservative evangelical serious Bible students.

- The KJV is the Bible of fundamental, independent Baptists.

- The HCSB is the Bible of Southern Baptists.

- The NLT is the Bible of seeker-sensitive evangelicals.

- The NET Bible is the Bible of computer nerds.

- The NRSV and CEB are the Bibles of Protestant mainliners

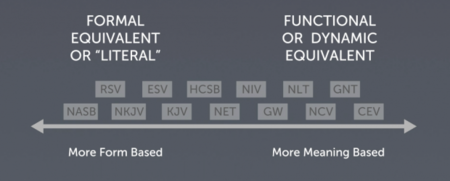

There is probably a little truth in every one of these somewhat tongue-in-cheek stereotypes (except in the ones you don’t like, of course). There really are different groups in Christianity, and they really have differences. It’s not completely accidental that each of these groups would gravitate toward particular translations. And I’ve argued before that the common translation continuum is, though potentially misleading (because all translations use a mixture of both “literal” and “dynamic” renderings), still genuinely useful as a rule of thumb:

But get that thumb out of your mouth, because it’s still wrong for Christians to be suspicious of other Christians just because of the Bible translation they carry to church. The tribalism needs to stop. All Bible-loving-and-reading Christians need to learn to see the value in all good Bible translations.

People who use the NIV exclusively need to also see the value of the NASB. People who use the ESV exclusively need to discover the help the NLT can provide. People who are KJV-only need to stop seeing the translation work of godly, careful brothers and sisters in Christ—such as Doug Moo of the NIV and Wayne Grudem of the ESV—as threats but as gifts.

To say “I am of the NIV” is wrong. To say “I am of the NASB” is wrong. To say “I am of the ESV” is right and proper and everyone else should wise up, you compromisers!

No, wait, wait . . . Give me a moment to breathe deeply and count to 10. Hey, I’ve got my own preferences. But I’ve officially given them up for your sake. And my own—because I actually think that the existence of multiple English Bible translations is a benefit to us all, not a justification for banner-hoisting and wagon-circling.

Trusted voices on translations

Bible translation tribalism doesn’t begin with a wicked desire to divide God’s people. It starts with a simple fact: translations are complicated things, and very few people have the expertise necessary to thoroughly evaluate them, let alone produce them—so the Christian consumers whose buying dollars determine which translations are successful are forced to trust “experts” when deciding which translation is best.

And whom do we trust? Generally speaking, we look to and trust our pastors for this kind of expert guidance. Hopefully, our pastors have a good grasp of translation theory and a lot of experience working through Scripture texts in Greek and Hebrew (Logos Bible Software exists for just this kind of work). But pastors who have done this work are actually more likely to realize that translations are complex. So they, too, trust others’ judgment. They trust their peers, their professors, their denominational leadership, their favorite Christian writers and scholars. This trust is completely natural and fundamentally good. We all trust authorities all the time to help us make decisions on issues that are too complex or would take too much time to grasp. I know my job, you know yours. But we all outsource other jobs to the experts. We try to be well-rounded, and we develop “informed opinions” about many topics, but we’re never going to be as informed as the experts in any given field. We simply don’t have time go around constantly doubting the work of the economists, civil engineers, chemists, optometrists, and Bible translators whose work we rely on.

If there’s a better recipe for highway asphalt out there than the one our municipality is using, we’re just going to leave that in the hands of the highway commissioner and drive on our roads anyway. If the textual critical issue in Jonah 1:9 could have been handled a little more adroitly; if the relationship of tense and aspect in Mark 4:13 fails to reflect the latest scholarship coming out of Steve Runge’s office; if there’s a more suitable rendering for rāqîaʿ in Genesis 1:6—99.9% of Christians, 99.9% of the time, will leave those issues in the hands of the experts and read their Bibles anyway. We will still trust our favored Bible translations, because people we have every reason to trust told us we should trust those translations.

But that’s just what the people in the church down the street, those false “Christians” with their wicked “Bible” “translation” (and their funny hair!), are doing. They’re trusting their leaders. So why are we better than they? If there’s a difference between “us” and “them,” it’s not that “we” are sitting down in a lengthy series of congregational meetings with all our Greek and Hebrew Bibles on our laps and hashing out all the differences among translations, and “they” aren’t. We should be content, without believing our translation to be perfect, exactly, to trust that it is reliable without condemning those who have made a different choice. Our pastor (and/or our crowd) decided translation X was best. Fine. We shouldn’t let our preferred translation become a symbol, a rallying cry, a boundary marker separating us from other groups within the body of Christ.

A way out of Bible translation tribalism

It’s the idea that we must determine which translation is best that has divided us into translational tribes. The need to pick the be-all and end-all Bible translation, the one that is simultaneously literal and understandable and beautiful, the one that (as one press release for a major translation claims) “eliminates . . . the tradeoff between accuracy and readability,” is creating a barometric pressure that is unnecessarily heating up the whole topic.

English speakers are looking for the wrong thing when we look for best. As I said, we need to look for useful. Does that sound too pragmatic? Let me clarify. We need to ask, “Which English Bible translation is most useful for preaching?” “Which is most useful for evangelism?” “Which is useful for reading through in a year?” “Which is conducive to close study?” How about for reading to kids? For memorization?

The average Christian has umpteen Bibles at home; we can afford, financially, to buy different editions for different purposes. Many of us have Logos, with its even greater number of Bible translations.

Because of our embarrassment of financial and translational riches, we can get very specific in our search for useful. “Which English Bible translation is most useful for preaching to these particular people?” “Which English translation is most useful for evangelizing this person I just met?” “Which one is most useful for reading through this year, given that I just read a more literal/paraphrastic version last year?”

A Bible translation thought experiment

Imagine there was only one English Bible translation and that it had never occurred to you that there might be another. The truth is that even if we were stuck with your and my least favorite translation on the chart above, we’d still have an inestimable treasure. We would still have God’s words. The KJV translators, in a sadly neglected but eerily prescient preface to the KJV, said the following:

“We do not deny, nay, we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English set forth by men of our profession . . . containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God: as the King’s speech which he uttered in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian, and Latin, is still the King’s speech, though it be not interpreted by every translator with the like grace, nor peradventure so fitly for phrase, nor so expressly for sense, everywhere.”

Read in Logos.

The KJV translators had no qualms saying that even relatively poor translations don’t just contain God’s words but are God’s word. They were not Bible translation tribalists. Perhaps we should take a page out of their book.

Mark L. Ward, Jr. received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the church as a Logos Pro. He is the author of multiple high school Bible textbooks, including Biblical Worldview: Creation, Fall, Redemption.

No comments:

Post a Comment